I submitted my very last paper of undergrad last week, entitled “Octavia Butler’s Archive of the Future”. For a class on the relationship between historiography and literature, I sought to return to my beloved Parable of the Sower and consider how Butler’s speculative writing simultaneously functions as historical writing. Thinking about the context when she wrote it, I tried my hardest to dig into the neoliberal optimism of the 1990s: specifically, the growing fear of an America where white people would eventually become a minority. I tried to work my way through Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism, spending far too long on just a few dense, beautiful paragraphs of affect theory.

What kept catching my eye as I worked was not the complex research on How Everyone Felt in 1993. It was my imagination of what Butler’s home office looked like. What her day to day looked like, and how she felt constantly imagining new worlds that appeared so different from our own. What was inside her giant file cabinets.

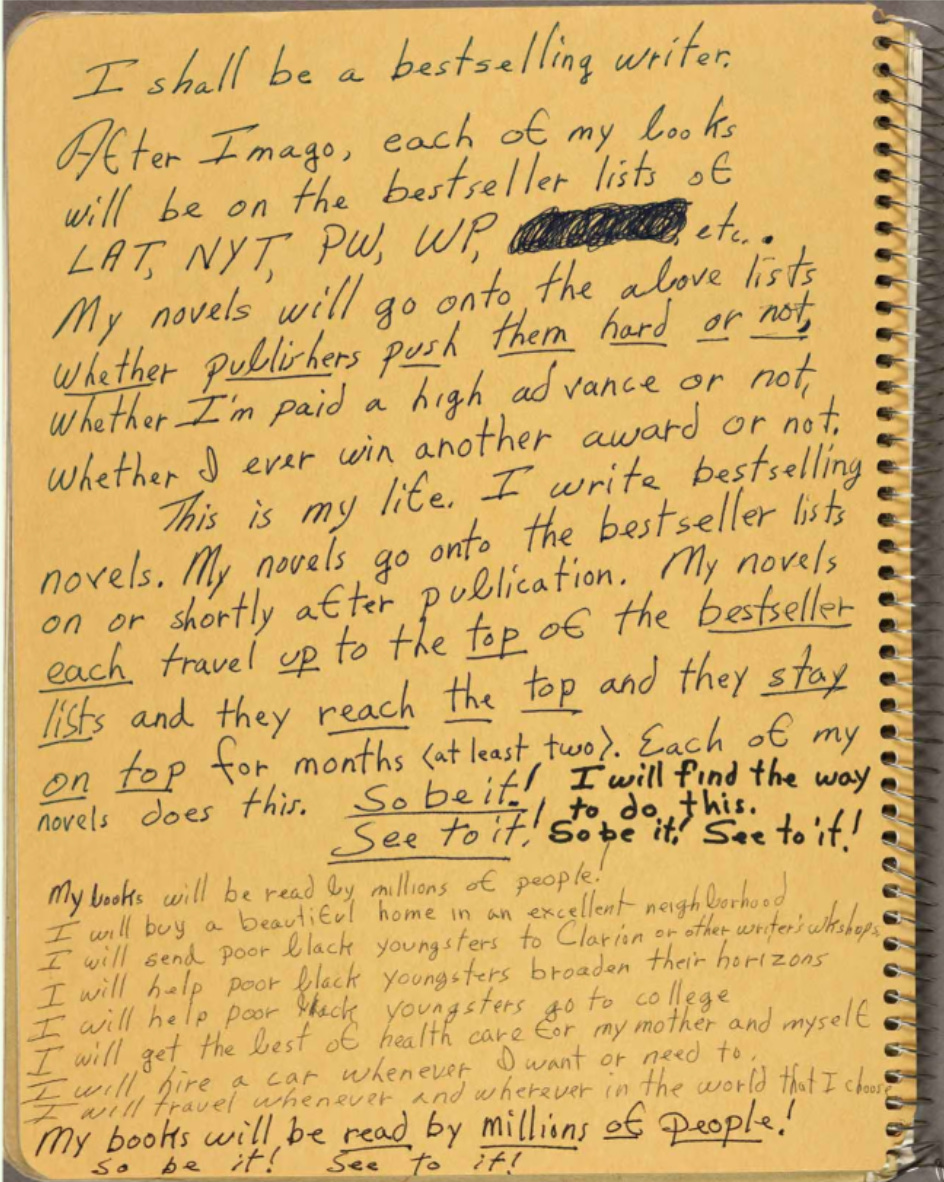

Perhaps the most well-known pieces of Butler’s extensive archive are her journals, all on display at The Huntington Library in Pasadena. Many have found inspiration in her firm commitments to herself and her success. Butler had an unwavering faith in her ability as a writer.

How lucky we are to have access to all of this information. These are just the most famous clippings of a life’s worth of journals. The religious verses of Earthseed, Lauren Olamina’s faith in Parable of the Sower, feel right at home among these pages. God is Change, Lauren writes, over and over again.

Butler confirms this connection in some journal somewhere. These verses are perhaps heightened writing exercises that Butler used to motivate, affirm, and calm herself. Butler’s personal rituals become the grounding force of a new world rising in Parable of the Sower. I am reminded of when I saw Toshi Reagon speak after a performance of Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower, her opera adaptation of the novel. Reagon was asked (by adrienne maree brown, nonetheless!) how she takes care of herself while working with this material. Reagon responded with something to this effect: I take care of myself by knowing that I speak the truth.

What has stayed with me even more than the journals is Butler’s letters. Not only does she have a fascinating collection of notes from other people, Butler made a copy of each letter she wrote before sending it, so that she would remember what she had said. Once she began using a computer, she printed out her emails after sending them. She recorded phone messages, then probably played them back so she could write them down. She wrote down descriptions of things she had taken pictures of. It seems that everything she encountered, she wanted written down on physical paper, stored in a file in her home.

Butler kept organized news clippings on a variety of issues that concerned her, most of which came up in her novels. Climate change, racist violence, gentrification, homelessness, crime—she called herself a “news junkie—as a way to fix the world”. She committed herself to taking in current events as a habit and practice, and keeping physical track of the pieces that felt important.

And like me, Butler walked. I broke my headphones at the beginning of this year and have been primarily walking without something in my ears for the past few months. Butler did not drive in Los Angeles, California: she walked and took the bus from her home to school and around the neighborhood. On September 19, 1992, she wrote the following in her journal:

“Magnolia trees

Mention grains

More expensive acorn

Trees here and outside

Magnolia trees are dropping

Their elongated lollypop seed pods

Camphor tree

round smooth berries and berry branches–tiny

Are still green.”

Not only did she carefully take the time to notice and write down what was going on in her neighborhood, she knew the names of the trees and plants. She found a comfort in the simple poetry of her mundane surroundings. Every front yard was an oasis; every tree, some kind of miracle.

There is an entire collection in her archives called “Coastal Scenes and big trees”. It is full of photos of the evergreen trees of the Pacific Northwest, where she spent the last few years of her life, and the trees that line the Tambopata River in Peru, where she traveled to research her Xenogenesis trilogy. In her time travel novel Kindred, jumping between the 1980s and the antebellum period, an ancient Wye Oak seems to tie the time periods together.

Phoenix Alexander describes Butler’s use of archive as “a space in which the prescriptive boundaries of genre—both literary genres and genres of the human—can be pushed to their theoretical limits and merged to create new and more hospitable forms.” Butler imagined the inhuman, grotesque, and fantastical to include elements of the human present. With each novel, she invited new species into the bounds of normality and the hearts of her readers, retelling the central political and emotional stakes of the moment in an unfamiliar context. This helped me consider how Parable of the Sower is simultaneously historical and speculative. Though it was Butler’s first novel to remain within the laws of physics (no aliens, vampires, etc), the central fears of what many readers call a “dystopia” came from very real moments Butler had witnessed.

Lest we forget, most characters in Parable of the Sower refuse to acknowledge the realities of world around them. The first half of the book takes place in the mid-2020s, within the walls of an eleven-family gated community on the outskirts of Los Angeles. Fifteen-year-old Lauren Olamina is scared. Her community is safe, for the moment, with barbed wire flying high over the fence. She and her neighbors have learned to grow food forests in their backyards and make flour from acorns. It rarely rains; shoes are expensive and hard to come by. They are not rich, but richer than many. Lauren knows that eventually, the “street poor” beyond the wall will succeed in their efforts to overtake the community. She knows eventually, her safety and resources will be lost at a moment’s notice. This truth is terrifying to Lauren—mostly because no one in her world will agree with her. They remain hung up on the fantasy of better times, imagining that they will sit back and wait for the good life to come to them. When Lauren confides in her friends about these truths, her friends go tattletaling to their parents. Lauren promises that she will survive whatever happens; and still, she is very lonely.

I thought about Butler’s archival practice in the context of longing and loneliness. Particularly as it’s transmuted through Lauren, this feeling that resonated across the research has stayed with me. I write at length in the paper about Butler’s correspondence with other Black women writers of the moment—most notably Toni Cade Bambara and Toni Morrison—and Butler’s loneliness as the only Black woman she knew writing science fiction. She proposed that many of her peers to dip into the genre and help her make the work more widely acceptable. She offered them help. She tried to make them understand how lonely she sometimes felt, and her many doubts about becoming a writer in the first place. Most of these propositions to her fellow didn’t seem to materialize into written work. Though she inspired many younger writers, Butler remained the only Black woman science fiction writer of her time.

Longing and solitude have been central feelings in my 23 years of life. What a surprise that this is how I connect to Octavia Butler. Long before I knew what it meant to be lonely, or left out, I found comfort in stories. Books, music, making things up and writing them down. Often wishing I had a friend to do it all with. I was perfectly happy to play on my own at kindergarten recess; eventually, I figured out that the other kids were looking at me weird. From there, and as things got harder at home, I started feeling lonely. I didn’t understand why other kids would rather give me weird looks than come and ask me what I was doing. It morphed into a long-lasting feeling of wanting to be part of everything. I wanted to belong. Still do!

Though we have lived very different lives, Butler’s feelings have been with me as I’ve written this paper. I have even wondered, as I often myself, how much of her isolation was the exclusion of others, and how much of it was a narrative in her head. Some of Butler’s writing to her peers could be blunt; in a letter to Bambara, Butler said that Bambara’s handwriting was terrible. Did Butler already assume she wasn’t liked by some of her peers, or that there was no possibility of friendship? The handwriting comment may have just been her style or sense of humor. Like me, though, she seemed to understand herself as alone, and often as lonely. It seemed to be difficult a lot of the times, and it also seemed like her way of going about the world. I get her. A lot.

As I leave school, with lingering questions about what I want my web of love to be, I’ve been thinking a lot about Butler’s archives. They are promises. To nature, the imaginary, the people around her, and most importantly herself. As I’ve said before, I believe memory is an intentional practice. Forgetting tends to be as well. This is not to say we always remember and forget on purpose, but I firmly believe that we can develop the habit of taking in the moments that we want to keep, and blocking ourselves from the moments we never want to see again. Butler wanted to know everything. She wanted to understand the world so that she could see beyond its possibilities. She wanted to remember herself and what she thought at a given moment, about friends, flowers, and politics. What struck her eye enough to take a picture, and how it looked, even with the picture right there.

Memoricide refers to the desecration of memory. It is the deliberate forgetting of culture; I first heard the term used by Palestinian fashion designer Yasmeen Mjalli, of Nöl Collective. I wonder, as we take each other’s hands against the settler-colonial fascist empires of the world, if we might give more attention to our own memories. Governments and citizens alike try to alter our understandings of our own history every day. Trauma causes amnesia; we struggle to capture the truth of these intense feelings and terrible things that have happened to us. This is exactly what they want, and Octavia Butler refused to let it happen. So I’m taking it with me! And trying not to forget.

Further reading:

https://doi.org/10.5621/sciefictstud.46.2.0342

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/theres-nothing-new-sun-new-suns-recovering-octavia-e-butlers-lost-parables/

https://www.latimes.com/travel/newsletter/2023-08-17/octavia-butler-nature-walk-altadena-pasadena-the-wild

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/tracing-octavia-butlers-footsteps-interview-rochell-d-thomas/

https://www.huntington.org/verso/octavia-e-butler-community-then-and-now

https://www.democracynow.org/2021/2/23/octavia_butler_2005_interview

https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2014/07/when-goddesses-change/

Thank you for this beautiful piece, Jack. I just mentioned you in my post today about the week I spent learning writing with Octavia. Congrats on completing undergrad! Wonderful writing.